Making (sense of) space

Virtually every organism on the planet has a sense of space. For us, this sense of space is vital not only to how we perceive the world, but how we think and act on it.

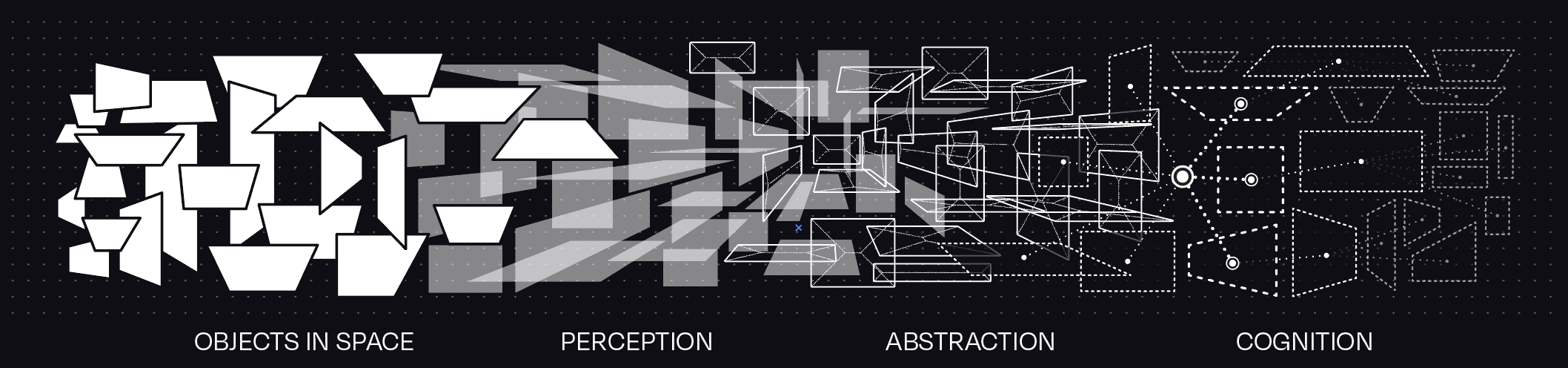

Objects in Space

There’s physical objects in space out there in the world, and the job of our sensory and perceptual systems, first and foremost, is to figure out the most reasonable interpretation of that structure.

Perception

That canvas in turn acts as a scaffold for higher-order thinking – crucial for our understanding of what it means for something to be complex, or random, for how we represent numbers and learn formal mathematics, and even how we understand what it means for something to be beautiful.

In order to make sense of the spatial world around us, we have to separate signal from noise, figure from ground, objects from scenes. In other words, our perceptual systems must take the ‘blooming, buzzing’ input that we receive and shape it into discrete entities – like objects and events, in space and time.

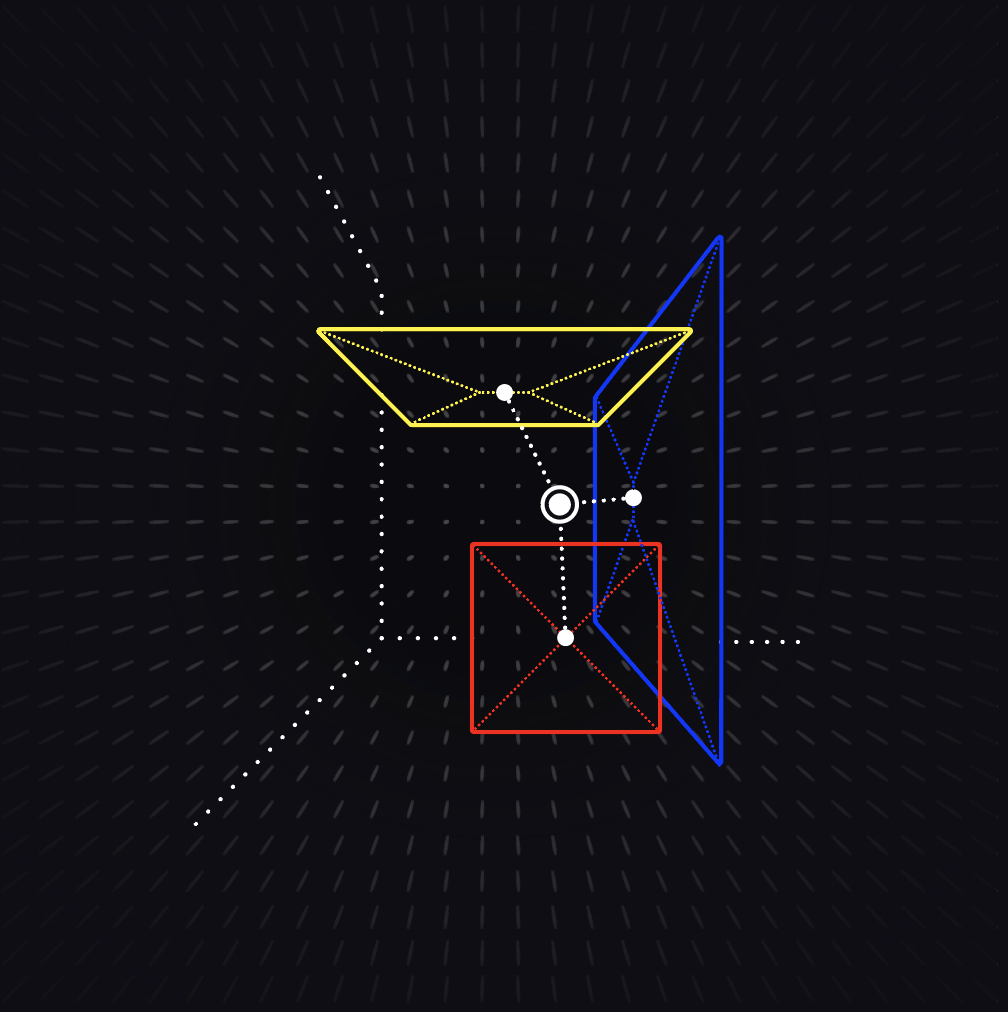

Abstraction

We can’t remember everything. Once we have a basic sense of the spatial world around us, we have to store that information in lower-dimensional formats. We extract things like the shape skeleton of an object, or the topological structure of an environment; these abstractions are stored in our minds for later use.

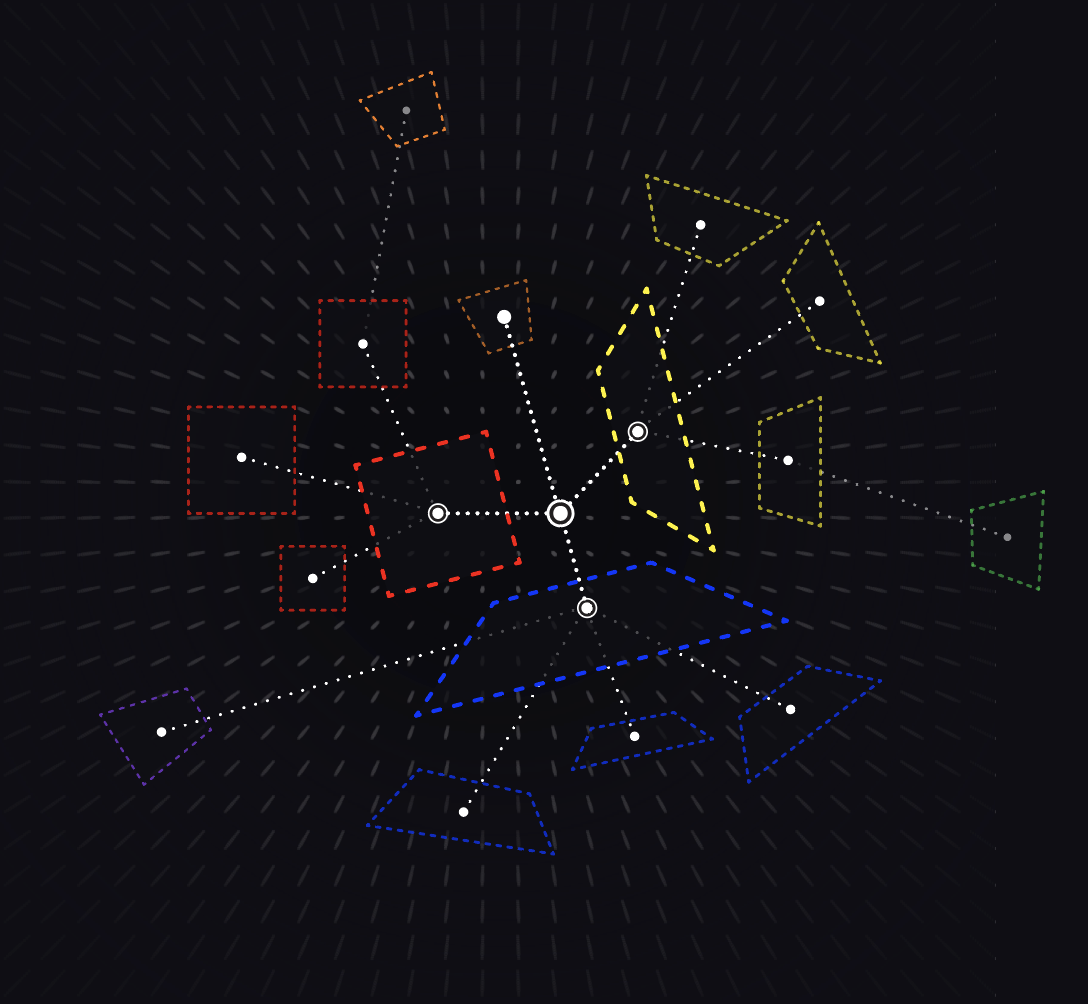

Cognition

The structured, abstract spatial representations that we create then support how we think about the world around us. Having an operable representation of an object allows us to rotate or manipulate that object in our mind. Having a sense of our spatial environment allows us to derive novel shortcuts through space. And perhaps most importantly: The space that we create in our minds acts as a canvas for us to organize our thoughts.